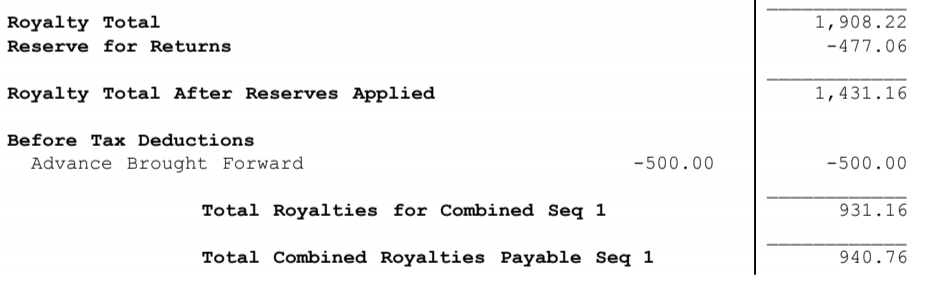

I recently received my very first royalty check for my book, Raw Material. Almost one full year after publication, and thousands of copies sold, I received a check in the mail for $940.76. Here’s a picture of the royalty statement:

When the publisher, Oregon State University Press, accepted my manuscript in December 2017, I received a check for $500 against future royalties, shown as a debit above. To date, I have received $1,440.76 for writing and publishing Raw Material (including my DIY Index).

It is surely not nothing, that $1,440.76. It’s also not as much as people expect for several consecutive years of work. It is as much as I earn in a handful (or less) of shearing jobs. It is money I never counted on having (and not just because royalties cannot, of course, be calculated in advance), and so did not count, budget wise. And it is money that other people — my publisher and customers — have paid for what I will call “my art.” The term feels too grandiose, but it makes the point.

I looked at that check, folded and unfolded it, tore the perforation and mobile deposited it. What to do with that $940.76 I received for my art? It felt like it ought to be for art, cosmically earmarked, if you will – pay it forward, pay someone else for their art. But what?

Not books, odd or unfair as that may seem. Perhaps it was too obvious for a book royalty check. I spend plenty (too much) on books each year, and am a regular at my local library branch. Likewise yarn, knitting patterns, journalism (subscriptions, ProPublica donations), and other writers’ writing (via Patreon). I save, and I donate a lot of time and money to charity each year.

The royalty check was different. It felt like it should go to something different and, ideally, art that represents — in some way — my life that is so different now than it was in 2015 (when I quit my day job after two years of side-gig shearing, and buckled down on Raw Material), and unrecognizable to what it was in 2012, before I attended shearing school. I wanted art that reflects the way my life looks now — not from the outside, not what someone else believes my life looks like, but from my point of view and, obviously, an artist’s point of view.

Yes: I wanted some of my days seen, artfully. Representation matters, and I rarely see my labor — and the labor of so many people who work on and with and throughout this land — or the feeling of living it represented in art. That absence often conveys an idea, which expresses a value, which is that certain people, labor, and ways of living are not worth representing in art. And that includes rural places and people, among whom I can only count myself partially at best, and then only part of the time. But I deeply appreciate and value them both, very much.

I found that art, by way of acquaintance with a wonderful writer named Quinn White, who is married to a painter named Matthew White in Kansas City, Kansas. And Matthew White’s watercolors not only looked, but felt, like the shearing life, especially the most invisible and unappreciated aspect of it: being on the road. The twin feeling of incessant, lonely, driving and wide-eyed, slack-jawed awe at this land, the light, its weather.

By this I mean:

And:

The power lines. The distance. Everything about these sings the hallelujah of being out in this glorious world while it’s still here, bruised or frozen as it and we shearers may be, meeting the folks in those houses and the sheep, just beyond, not yet herded and driven, the tips of their fleeces gathering fog and frost.

I can’t really put it into words, which is why it needs to be painting.