If you’d like to try sheep shearing, where do you start?

Not on YouTube or TikTok. Shearing cannot be taught solely or even primarily via video. That would be like trying to learn figure skating by video, without ever having set foot on ice. Video cannot convey weight, power, force, momentum, resistance, balance, temperature, and duration, much less all of these simultaneously. A video cannot convey how gentle a physical motion is, that may appear rough (or vice versa).

You must go to shearing school, or at least apprentice, and ideally go to shearing school and then apprentice, on at least a few jobs with other shearers. Shearing school will introduce and connect you with other shearers, and these folks will open doors to what is actually a very small world, even globally. You will make friends for life.

How To Find Sheep Shearing Schools

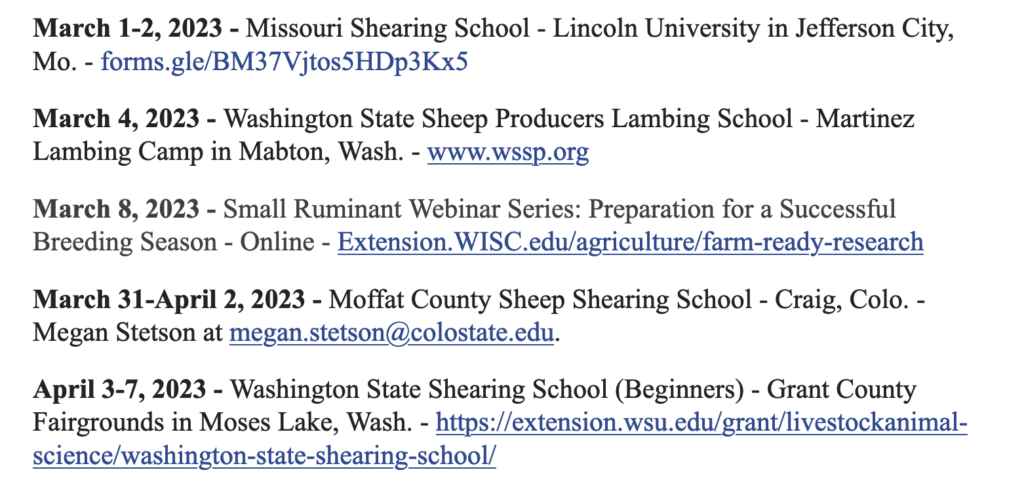

The American Sheep Industry Association (ASI) website is the best place to begin, and specifically with their newsletter. Each week’s ASI newsletter includes a list of Upcoming Events, which includes shearing schools. Most shearing schools in the U.S. take place in spring (because sheep get sheared before hot summer arrives), last for three to five days, and cost $250-$500. Scholarships and financial assistance are often available. If these are not explicitly mentioned, ask!

In addition to the ASI Newsletter, sheep and wool growers’ associations, and agricultural schools and extensions often sponsor sheep shearing schools. Some of these organizations also maintain directories of sheep shearers for their members to find, to which you can add yourself later. If you live in Montana, for example, you may want to join (or at least subscribe to the newsletter of) the Montana Wool Growers Association (MWGA), even if you are not a wool grower yourself. This will introduce you to sheep-related events, trainings, and other shearers with whom you might work.

You can also search online for “shearing school” + the name of your state, but the results are not always great. Algorithms favor mainstream popularity and many not handle niche content well or accurately. If you don’t find a reasonably nearby shearing school via a search engine, do not be discouraged.

A few days of shearing school will tell you if it’s something you want to do, and can physically do, going forward. Get through shearing school first and then think about what’s next.

Sheep shearing is a full-body experience. Your legs have to hold and move a sheep that weighs 100-250 pounds while one hand pulls its skin taut and helps control and move it, all while shearing with the other hand (and sweating like mad while your back screams). Animal handling and equipment selection and set-up are 90% of safe, humane shearing you can be proud of. You do not want to hurt an animal or yourself, and it’s easy to do both if you haven’t learned from experts, hands on. The shearing strokes are the easy part, the fun part, the pay-off for all the hard, consistent, frustrating work you put in elsewhere.